Alma Zohar & Nitzan Hen Razel – The Poem Of The Grasses

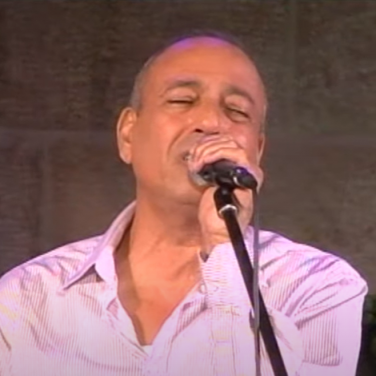

Akiva Sygal

The poem of the grasses

Naomi Shemer | According to Rabbi Nachman of Breslav

Translation credit: George Jakubovits

hebrewsongs.com

Do know that each and every shepherd has his own tune. Do know that each and every grass has its own poem. And from the poem of the grasses a tune of a sheppard is made How beautiful, how beautiful and pleasant to hear their poem. It’s very good to pray among them and to serve the Lord in joy And from the poem of the grasses the heart is filled and yearns And when the poem causes the heart to fill and to yearn to the Land of Israel a great light is drawn and goes from the Land’s holiness upon it. And from the poem of the grasses a tune of the heart is made.

If it were possible, I would have liked to go and interview an old shepherd living in the area of the town of Uman, in Ukraine. This old man would surely have told me of the Jew’s grave in his town, and remembered how, in his childhood, a group of Hassidim would arrive, making their way to the grave of their holy rabbi every year around September. He would go on to describe how the stream of visitors grew over the years, in recent years becoming a flood of tens of thousands of people, and how this year the event went back to being as it had been in his childhood – just a handful of Hassidim. I wonder how the spectacle would be seen by this old man, who has nothing in common with Hassidism other than their shared geographic space. For us, this has become a major occurrence in Israeli society in recent years. Its origins lie in the fact that, somehow, the teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov – who lived 250 years ago in Ukraine – appear to have been written especially for the modern heart in 21st century Israel. In his day, only a handful of Hassidim felt a connection to these teachings and followed him, while in our times many live by his doctrine and feel that this is their path in Judaism. One can only imagine the frustration of Rabbi Nachman with the fact that not many understood his doctrines and connected to the emotion in them during his lifetime, and how he would feel if he lived in the new-age times of the past 20 years, when he stars in every corner of Israel. And yet, the sayings of Rabbi Nachman penetrated Israeli culture through song even earlier, in the 1970s, when two of his axioms were the basis for two very well-known songs. In 1974, at the height of the Yom Kippur War, the American rabbi Baruch Chait set the sentence “All the world is a narrow bridge” to music. Singer Yehoram Gaon sang this song to the soldiers on the front line, and also recorded it for radio, and the rest is history. Two years later, Naomi Shemer was asked to write songs for a musical by the name of “The Travels of Binyamin the Third”, based on the book of this name by Mendele Mocher Sefarim. In this context, Shemer wrote and composed the “Song of the Weeds”, based on two separate teachings of Rabbi Nachman. I marvel at how, at a time when Rabbi Nachman was still far from the heart of Israeli consciousness, this symbol of Israeliness in herself, from Kvutzat Kinneret, comes along and chooses to compose a tune for his lyrics, let alone a song intended for a satirical play. But Shemer was prophetic, of course, since the play sank into oblivion long ago, while the song has become an unchallenged asset, and perhaps it was this that first brought Rabbi Nachman’s teachings to the Israeli public. There seems to be a connecting line here between Rabbi Nachman back then in Eastern Europe, and Shemer in Israel of the 1970s; and this common thread is the intimate, mystical, almost romantic connection – to nature. Rabbi Nachman spoke extensively about going out into the forest as a practical way of talking to God and strengthening faith. Many of the songs of Shemer, who grew up in a kibbutz near the Sea of Galilee, contain very rich descriptions of the world of nature, indicating an intimate acquaintance with this world. Belief in the fact that the singing of the weeds is what creates the poetry of the shepherd, that it is nature that gives birth to poetry in the heart of man, this is what unites the Hassidic Rebbe and the secular poet. It seems that for her, as for Rabbi Nachman, going out into nature is not just a random trip or respite: it is a source of inspiration and connection to God. This message is sharpened in the second verse of the song, which is based on another conversation of Rabbi Nachman:

How lovely,

How lovely and beautiful it is

when you hear

their singing.

It is very good

to pray amongst them

and to gladly serve

the Lord,

And from the singing of the weeds

the heart is filled

and yearns.

Nowadays, when the study of Hassidic teachings in secular study frameworks is so popular, it is easy to be tempted to bring universal messages such as connection to nature, and cut the picture to the page of sources just before more “religious” talk about God’s work or the holiness of Israel among the nations begins; no one will know what there was in the original that you did not quote. But part of the secret of the song’s charm and reception is that Naomi Shemer, even though she herself is not religious, does not try to secularize it. She leaves not only the general word “to pray”, but also the clearly religious expression “to worship the Lord”. One word she did change: Rabbi Nachman is quoted by his student and the author of his books, Rabbi Nathan of Nemyriv, as saying: “How lovely and beautiful it is when you hear their singing, and it is very good to pray amongst them and to worship God in awe”. Naomi Shemer replaced the “awe” with “gladly”, a change that is completely in line with the Hassidic spirit and the spirit of Rabbi Nachman himself..

And when the heart

is filled by the singing

and yearns

for the Land of Israel,

A great light

then goes on and on

from the sanctity of the Land

upon it.

The third verse is already an addition that Naomi Shemer has made of her own accord – Rabbi Nachman spoke in many places about the sanctity of the Land of Israel, but did not connect the Song of the Weeds to it. Here the difference between them is also revealed: Rabbi Nachman heard his shepherds’ song in the expanses of Eastern Europe, the shepherds he heard were not Jews, and the landscapes were not Israeli. Naomi Shemer’s connection to nature was formed here in Israel, and it seems that for her, the connection between the weeds and holiness happens only through the mediation of the Land of Israel, and perhaps what gives the shepherd and his melody a dimension of sanctity is actually the holiness of the land. The day of Rabbi Nachman’s death is marked every year on 18th Tishrei, that is, during the intermediate days of Sukkot. Sukkot is the holiday that takes us out of the house, and the Sages have already noted that it does not take us outside in spring, when all of nature is blossoming and flowering, but rather at a time of closing in, when summer has already killed the green, but the rain has not yet created regrowth. During this period we do not go out into nature to enjoy its fruits or blossoms, but because nature itself revitalizes us and connects us to God; in the absence of flowers and butterflies, all that is left is to listen to the singing of the weeds.