Life defeating death

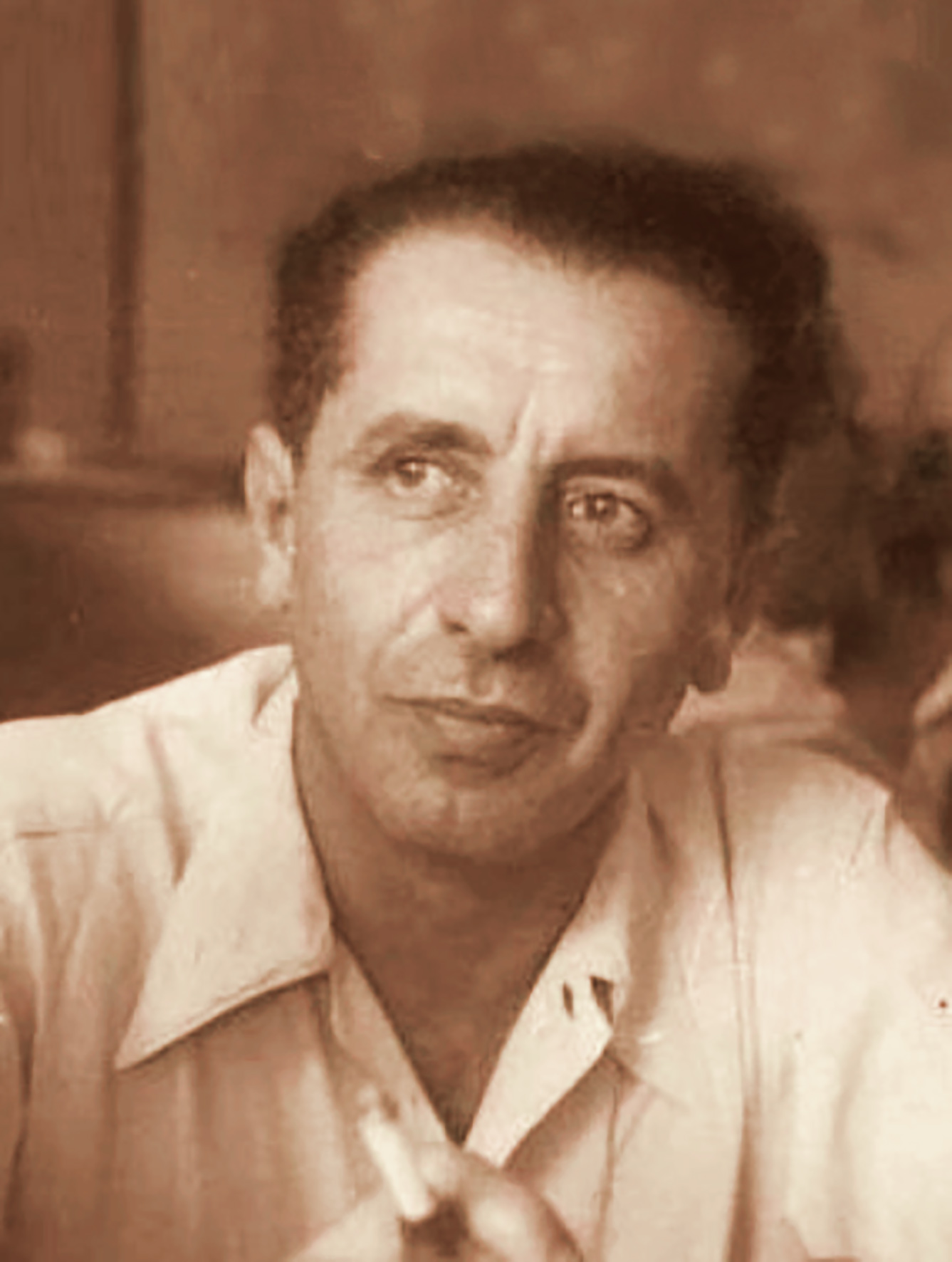

Tsur Ehrlich writes about Natan Alterman

צילום: shutterstock

צילום: shutterstock

Just before the end of “The Joy of the Poor”, the city falls. Yes, literally: The final poem in Natan Alterman’s “The Joy of the Poor” cycle is called “The End”, a poem of coming to terms with death but also victory over it, ending with the eternal phrase “not everything is vanities and vanity”. And the poem before it, Chapter 7, is “The City Falls”.

The city falls after a siege, and following a desperate defensive battle. What is the city? “The Joy of the Poor” – the most important work in modern Hebrew literature, a noble and majestic prophetic poem encrypting the code of our existence – is a great riddle, a multi-faceted symbol, for which many interpretations have been given. Some place it in a Jewish context, and some in a universal context; some emphasize the fact that it was written during World War II, while others less so – but what they all share, in line with the explanation of Alterman himself, is that the city that is defending itself embodies what is human, what is good, and precious, and noble in life.

“The Joy of the Poor” is filled with echoes from the Jewish sources – and especially from the Bible, the liturgy, and the yearly prayer cycle. And here is the epic climax, the moment of destruction and curse before the hope of redemption, the poem “The City Falls”, a whispered hint of two episodes in the Jewish year; two episodes of abstinence and fasting. Of Bein HaMetzarim, the three weeks before the fast of Tisha B’Av, the days of mourning for the destruction of the Temple – and the fast of the Day of Atonement. And this is interesting.

The connection with Tisha B’Av, with destruction of the Temple, is manifest. Siege, struggle, destruction, exile. But it is much more than this. Tisha B’Av comes here with its emancipatory bonus. Even “בין המצָרים”, mentioned here explicitly, is also a source of hope, and therefore of happiness: “By our poverty’s might, I swear”, that is, I swear by the power of our poor, “in distress / not the victor – the victim knows happiness!” The besieged, the despised and downtrodden worm of Jacob, it is they who will be laughing at the final accounting, and not those who pursue them. For it is they who constantly remember and strive, and therefore they will not be annihilated.

But more than this. The country is sworn not to forget the death of the fighters, and not to betray them, lest “the joy forget you”, the joy of the poor, as in “If I forget thee, o Jerusalem, let my right hand forget her cunning”, “and, like sunrise, come insult’s season / And the plowman, on fields that in weeping bow, / when asked by his fellow: What do you plow? / will reply: The soil of treason.” This description of the curse of the land hints at the Talmudic legend of the man plowing his field with his cow, who is told by an Ishmaelite on the 9th of Av of the destruction of the Temple – and of the birth of the Messiah. “Still, for salvation’s hope, you embraced the son.”

Out of the straits and the destruction, therefore, comes salvation. And this is the key to understanding the place of the other fast day, Yom Kippur, in this poem of destruction. Not as a day of atonement and purification does Yom Kippur appear already in its opening words, but as the climax of the “Days of Awe”. “Fearful Father”, he calls God. This same “El Nora Alila”(God of Awe) of the Days of Awe. And the poem immediately recalls the liturgy “We are but clay in the potter’s hand…”, by whose wishes our days are extended, and by whose wishes they are shortened: “Fearful Father, Preserver, and Death’s grim Reaper”. Yes, we are in his hand also on the night the city falls.

On this night of death we remember why we were born: “to Gladness and Joy”. And therefore with the loss comes joy, comes happiness. This is “joy ancient”, because “maybe, Brethren, once in a thousand years / for our death there is morning’s light!” This death, death for the sake of our common existence, may perhaps have a purpose. It is “once not in vain”. And how rare this is.

The Day of Atonement, Judgment Day, follows immediately after with the paradoxical cry “תַּעֲלֶה רִנָּתֵנוּ – אָבַדְנוּ!” [on Abbadon’s joy shines the light]: as in another Yom Kippur liturgy, “May our supplications rise at nightfall, our prayers approach you at dawn, let our exultation come at dusk”. But unlike Yom Kippur, our exultation is also in the face of loss. The same is true when it is hinted, in an inversion, that “the day has turned” in the Neila prayer: “Exultation shall reign, ah, for night’s on the wane / on Abaddon’s joy shines the light”.

Yom Kippur therefore bursts into this poem, through hints at its liturgies, as a terrible day of judgment, a day of “who shall live and who shall die”, of a sentence of death, and a sentence of life that is also a curse: “And God, life-giving / has cursed him to living!” But if Tisha B’Av has a hope of salvation – certainly Yom Kippur does as well. The worm that has already been mentioned, the worm of Jacob, the worm whose happiness, although bad for it, is also our sins, which, like on Yom Kippur, even if they may be red as a worm, will turn white as snow. Death also has a dawn and hope. The end of life, if even the life of the son, will defeat it.

Tsur Ehrlich is the deputy editor of the journal HaShiloach, an editor at Sifriyat Shibbolet, a poet, and translator of poetry and reference books.

“

ד תמר הירדני, באדיבות ויקיפדיה