Rabbi Haim Louk and the Piyyut Ensemble of the Ben Zvi Institute – Your Gates Open at My Knocking

Akiva Sygal

Your gates open at my knocking, Lord

Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gabirol

The two first stanzas

Your gates open at my knocking, Lord,

and you loan to the poor, before you, forgiving God.

My prayers and supplications will come before you,

in the place of lamb sacrifices, flour offerings, and meal offerings.

In Israel, it is a familiar cliché that every elderly Moroccan working here in Israel at any craft, did the same thing in Morocco at the King’s Palace. This cliché reflects a reality, in which in large parts of Morocco the Jews lived in exceptional proximity to the Arab world around them, formed an integral part of the cultural environment in which they lived, and even sheltered in the shadow of the king. This unique fabric means that in the sphere of music too, the world of Moroccan piyyut perfectly parallels the world of Moroccan Muslim music, with its multifaceted variety of genres. In fact, many of the piyyutim of Moroccan Jewry (of which there are several thousand!) have adopted a familiar melody with Arabic words. Therefore, in order to understand the world of piyyut of Moroccan Jewry, we must first get to know the world of Arabic music in North Africa; and in order to understand this, we need to return to the roots of Arabic music in general.

The inhabitants of the Arabian Peninsula were mostly illiterate before the advent of Islam. During this time they were very involved with poetry, but without writing: they memorized long poems, tens and hundreds of lines, that tell a story in rhyme – about battles, loves, and tribal tales. This art is known as ‘qasida’, and in time it was transcribed and spread throughout the Arab world, including North Africa. Musically, it is characterized by a simple melody that is not intended for embellishment and developed improvisations, but rather to accompany the textual story. Despite this, due to the length of the qasida, the melody may change a number of times according to the changes and developments in the plot.

At the other end of Arabic music is Sufi music. The Sufis are the mystics of Islam, who believe that love for God should be ignited in the human heart in physical ways. On this basis, the Sufis engaged in singing and dancing, repeating one word over and over again – such as “Allah” or “Muhammad”, at an ever increasing rate, while dancing. If the music of the qasida is simple because of the weightiness of the text, here the music is simple and the text is also negligible, in order to make room for the mystical experience created by the repetitiveness. The Sufis are known to have greatly influenced the sages of Mizrachi Jewry, the most significant and famous example being the book “Sufficient for the Servants of God” written by Rabbi Avraham ben HaRambam.

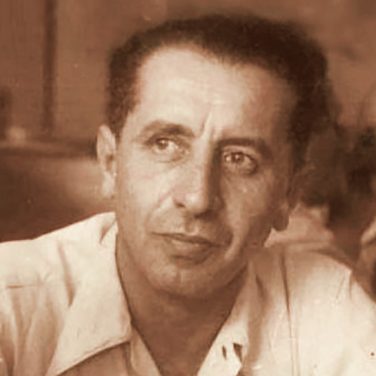

The Jews of Morocco in modern times were familiar with the rich and varied textual repertoire of the piyyutim, and they adapted them to the Arabic music around them – qasidas, Sufi songs, and also other genres. One who contributed more than any in the 20th century, and wrote lyrics for many of the Arab songs that were popular in Morocco, was the liturgical poet Rabbi David Buzaglo, who immigrated to Israel at the end of his life, and settled in the Krayot. Rabbi Haim Louk is a clear student of Buzaglo, and is undisputedly the most senior Moroccan liturgist in Israel today. In the video before us, he chooses to combine two liturgical texts, with two melodies from the same musical scale – Maqam (to borrow a term from the world of Middle Eastern music) Hijaz. The first is the familiar piyyut from the Selichot, “To you, O Lord, I lifted up my eyes”, and the second is a much lesser-known piyyut written by R. Shlomo Ibn Gvirol – “Your gates open at my knocking, Lord”. The two liturgies are textually different from each other: “To you, O Lord” is a relatively long piyyut, following the alphabet, sung at the end of the Selichot by the entire congregation, and therefore the melody must be relatively simple. It describes the wretched situation of the people of Israel in exile, asks for redemption and forgiveness, and also contains words of praise to God. By comparison with the long piyyut and its variety of topics, “Your gates open at my knocking” is a much shorter, monolithic piyyut giving clear expression to one idea – a liturgy that is entirely words of supplication, and it is written in singular form:

Your gates open at my knocking, Lord,

and you lend to the poor before you, forgiving God.

The different textual character dictates the adaptation to the melodies: the long and narrative “To You, O Lord” receives the slow and simple melody of a familiar qasida. Despite the length of the text, the melody does not change, and instead is sung more and more quickly throughout the song, until it ends at a pace that is two or three times faster than the beginning, a very common practice in Moroccan music. From here, Rabbi Haim Louk continues to the piyyut “Your gates open at my knocking, Lord”, to which he attached a Sufi melody in the same Maqam. The Sufi melody matches the personal supplication in the piyyut, and Rabbi Haim Louk even retains the words “Allah Allah” as in the Sufi source. In contrast to “To You, O Lord”, this adaptation is unfamiliar, and is probably already that of Louk himself, continuing the tradition of his teacher and rabbi of adapting piyyutim to melodies. But we have another surprise in store..

Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol’s poetry enjoyed a revival in 2007, when Berry Sakharof and Rea Mochiach teamed up with other musicians and released the album “Red Lips”, entirely comprised of poems by Rabbi Shlomo Ibn Gvirol. While in 2007 it was a real innovation to produce a rock composition for Ibn Gvirol’s thousand-year-old songs, in 2015 the members of the ensemble challenged themselves by taking another step, joining Rabbi Louk and the Andalusian musician Elad Levy, and participating in a performance of “Your gates open at my knocking, Lord” with a Sufi-Moroccan melody par excellence. The Sufi melody is intended to repeat itself over and over again until a feeling of transcendence; added to this here, between one repetition and another, are the rock beat and keyboard improvisations by the members of the ensemble, all veteran secular musicians in the field of jazz and Israeli rock. The melody returns, but the tone is new.

Thanks to the poet and Moroccan music researcher Chai Korkus for all the information.