The Evolution of the Sukkah

Ella Arazi

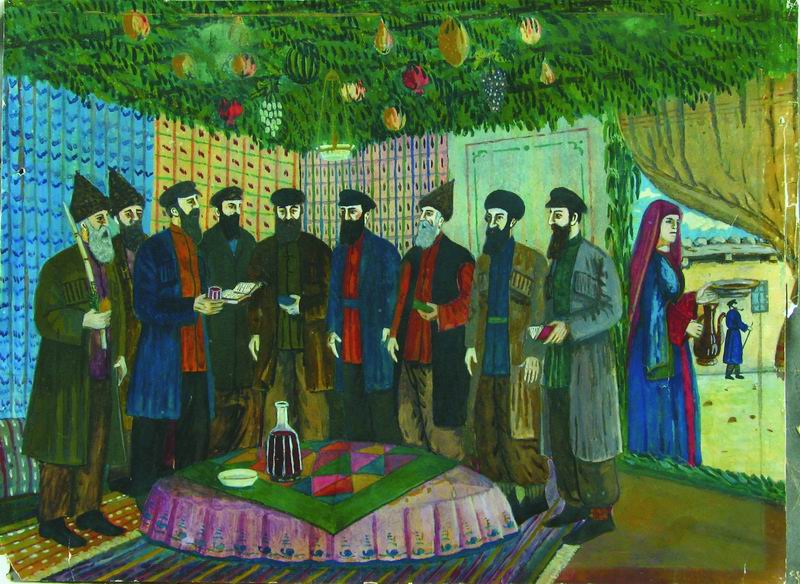

מאת שלום קובושווילי - ויקיפדיה

מאת שלום קובושווילי - ויקיפדיה

Ella Arazi surveys how the traditional Sukkah has changed from then to now

The Bible commands us to sit in the Sukkah: “Live in temporary shelters for seven days: All native-born Israelites are to live in such shelters; so your descendants will know that I had the Israelites live in temporary shelters when I brought them out of Egypt.” (Leviticus 23: 42-43). Despite these commands, the Bible doesn’t specifically mention that the Israelites sat in shelters during their wandering in the desert. Perhaps that’s why it says “so your descendants will know”, and not “remember” – your descendants shall experience the feeling of wandering. And the best way to feel like a wanderer is to sit in a sukkah, which is a typical characteristic of nomads.

What is that temporary nomads’ shelter, and is it similar to the holiday sukkah that has emerged through the generations? The origin of the word “sukkah” is in the Hebrew root “sakhakh”, which means “defense”. That root also created the words “Skhakh” (roof), “masakh” (screen), and “masekha” (mask). Nomads tend to build shelters for temporary sanctuary from climate conditions. They are built out of natural, biodegradable elements, like branches, stones, and mud to stick them together. They are created from scratch, and when they are no longer used, they go back to oblivion.

Farmers have also always built shelters, to protect their crops after picking. In this context, we know of the sukkah in the book of Isaiah: “Daughter Zion is left like a shelter in a vineyard, like a hut in a cucumber field, like a city under siege” (Isaiah, 1:8). Today we can also see makeshift shelters or shacks under which produce is sold by the side of the road. These are made out of recyclable materials such as sheet metal, cartons, doors, mats, canvas, boxes, and more. The holiday sukkah that has evolved through the generations is very different from the original, improvised version; it is built at a predetermined time and location, there are many rules to dictate how we build it, and above all – tradition has encouraged us to decorate the sukkah. The principle of beauty has created incentive, and the people of Israel build festive sukkot every year, that are creative and incorporate a variety of elements: plants, textiles, lamps, furniture, cushions, prints, murals, and more.

The earliest mention of designing a sukkah is in the book of Nechemia: “Go out into the hill country and bring back branches from olive and wild olive trees, and from myrtles, palms and shade trees, to make temporary shelters”—as it is written. So the people went out and brought back branches and built themselves temporary shelters on their own roofs, in their courtyards, in the courts of the house of God and in the square by the Water Gate and the one by the Gate of Ephraim.” (Nechemia, 8: 15-16). Like the nomads’ shelters, the shelters in the Book of Nechemia are made of natural elements, but unlike improvised shelters, in the Biblical description it is clear that there was an intentional effort to use wood from quality trees – probably the four species. The Samaritans also use wood from the four species to build the sukkah, or more accurately, the roof. They interpret “citrus” as any elegant fruit, and also embed a variety of fruit in geometric patterns on their thatch. Above the fruit are palm leaves, arava (Abraham’s bush) and thick wood (a branch from an evergreen).

An especially beautiful description of a natural shelter appears in the Talmud: “If one roofed the sukkah in accordance with its halakhic requirements, and decorated it with colorful curtains and sheets, and hung in it ornamental nuts, peaches, almonds, and pomegranates, grape branches [parkilei], and wreaths of stalks of grain, wines, oils, and vessels full of flour…” (Talmud Bavli, Sukkah, Daf 10 Page 1). The sukkah is decorated in a variety of fruits and food groups: grains, wine, and oils. But it is not only natural elements that appear in this description, but also textiles and colored sheets. These are the only elements that may be reused, and this is the first digression from the custom of the traveling nomad’s shelter. The sukkah made of colorful sheets was adapted to the Mediterranean climate and was therefore easy to maintain as a tradition in the East, renewing itself in Israel.

In Turkey and Syria, the textiles used were the curtains that covered the Holy Ark. This custom created a paradox: in order to decorate the sukkah, a holy ornament was removed of its holiness (the Holy Ark is more sacred than the Sukkah), which is forbidden by the halakha. Of course, the rabbis were ill at ease with this tradition, but their protests were futile – sometimes a custom proves more powerful than the established halakha.

Along with the natural and textile-built shelters of the

Mediterranean, European Jews developed a different architectural tradition: the cold weather, along with the obligation to eat and sleep in the sukkah dictated a need for massive wooden structures. Building such a structure every year is tiresome work (and that’s reserved for Passover, not Sukkot), which led to the creation of temporary booths that could be dismantled and rebuilt every year (the prototypes of the “Ever-Sukkah” sold today). These were decorated with murals, evergreens, and paper decorations.

Some of the sukkot had rooves with folding “wings” that could be completely shut when it rained, or on cold nights. Sometimes they went even further, and the sukkah was a room in the house or a balcony that had an opening for thatch, which could be sealed when it rained. Ethnographic studies of Eastern Europe found many Jewish homes with decorated walls, featuring graphics and texts associated with Sukkot.

The continuance of the European tradition can be found in the Haredi community. The sukkot are made of wood, although local climate doesn’t warrant this, and before the holidays, all sorts of temporary “extensions” appear, in an effort to connect the sukkot to homes. Often, this extension is so convenient that they do not immediately dismantle it after the holiday. The sukkot remain, enduring the cold and rainy days. Often we can see a sukkah boasting a Hanukkah lamp. We make haste to build the sukkah, but not to dismantle it.

The Jerusalem-style sukkot built on Sha’ar Hamayim and Sha’ar Ephraim streets in the time of Nechemia were only a few kilometers away from the sukkot built in Me’ah She’arim today. But an ideological abyss separates the two. How far that primitive shack was from the luxurious wooden extension we build today, how the principle of beauty has evolved, and the tradition of sleeping in the sukkah is so far from the original intent – to experience life as a nomad.

פלאש 90